Fiction Writing

Writing Fiction Texts in the 11+

Not all 11+ exams include a writing task, but some schools do ask children to write a short piece of fiction (usually just a few short paragraphs). This is often a story opening or a descriptive scene, though some schools may set tasks like continuing a story, describing a picture, or writing from a different character’s point of view.

This section will teach your child how to structure their creative writing and use language effectively to bring their ideas to life. It covers how to create believable characters, build a clear plot, and write vivid, engaging descriptions.

What is a Fiction Text?

A fiction text is a piece of writing that is made up.

Your child might be asked to write…

- A short story

- A short scene from a longer story

- A description of a setting

- A description of a character

- A diary entry based on imaginary events or written from a character’s perspective

Fiction is designed to entertain. When writing a fiction text, your child will need to use their imagination.

In contrast, non-fiction is based on facts, opinions or real experiences. Some 11+ exams allow children to choose between writing a fiction or non-fiction piece.

Knowing whether your child will be asked to write a piece of fiction or non-fiction can help them prepare with more confidence. Make sure you look at the past papers for your school to see what they will be asked to do. They might not need to complete any long writing tasks at all!

Understanding Writing Tasks

If your child needs to write a fiction text, help them practise with past papers and other creative writing tasks.

When reading the task, help your child underline the key words. These words will tell them what the text should focus on.

Most prompts are open enough to be interpreted creatively. For example, an ‘unexpected visitor’ could be a person, an animal, a memory, or even something like fear or guilt.

Key Terms for Fiction Writing

These terms can help your child plan and write stronger creative pieces. They don’t need to use all of these things in every story, description or imaginative diary entry, but understanding them will help you make their writing more effective and interesting.

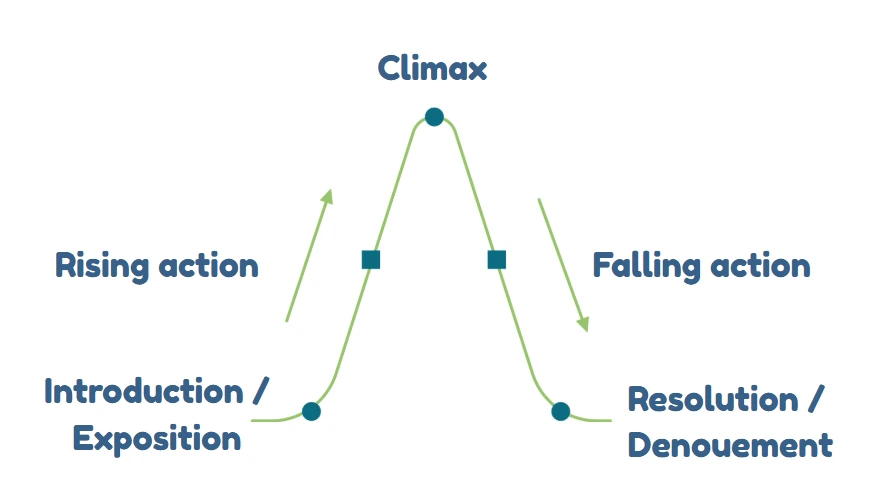

Plot

The plot is what happens in a story or diary entry. Good stories usually involve a problem or conflict that gets solved or changes by the end.

When it comes to the 11+ exam, keep it simple. The best short pieces of writing focus on just one moment or problem, rather than trying to squeeze in lots of characters, actions or ideas. Children don’t need to write a full novel. In fact, it’s better to zoom in on a single moment – a turning point, an encounter, or a challenge – and describe it in detail.

Example: In a short story about a lost dog, the plot might follow a child searching for it, getting more desperate, and finally finding it again with the help of a stranger.

Tip: Unlike stories and fictional diary entries, descriptions just focus on showing what something is like. There might be some action in a description of a person or setting, but there won’t be a fully developed plot.

Protagonist

A strong short story usually focuses on one main character in a story or diary entry- this is the protagonist. They are the person your reader will follow and care about most. The protagonist doesn’t need to be a superhero; they just need to feel believable. In short stories, the protagonist usually faces a problem or challenge and changes in some way by the end.

Tip: Encourage your child to focus on the protagonist’s thoughts, feelings and choices. Make them change, learn or feel something by the end.

Antagonist

The antagonist is the person (or force) that causes problems for the protagonist. It could be a mean character, a natural event (like a storm), or even an inner fear.

Example: In a survival story, a snowstorm could act as the antagonist.

Narrator and Point of View

When writing a story, it’s important to decide who is telling it.

- First person uses ‘I’ and lets the reader see everything through the main character’s eyes.

- Third person uses ‘he’, ‘she’ or ‘they’, and lets you describe more of what’s going on around the character.

Tip: First person often works well for emotional stories. Third person can be better to help you create suspense or describe action.

Setting

This is where and when your story takes place. A clear setting helps the reader picture the world. You can describe weather, time of day, surroundings, and even use the five senses – sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell.

Example: ‘The trees creaked in the cold wind. Ice cracked under her boots.’

Theme

The theme is the main idea behind your story. Even short pieces often hint at a theme, like friendship, identity nature, religion, bravery, jealousy, loneliness, growing up, and many more!

Tip: Don’t say the theme out loud – just show it through what happens.

Characterisation

This is how you show what your characters are like. Good writing shows their personalities through what they do, say, and think.

Direct characterisation: ‘He was shy and quiet.’

Indirect characterisation: ‘He stayed near the edge of the room, twisting his sleeves.’

Tip: Often, indirect characterisation is more effective. Use small details to show emotions or attitudes.

Conflict

All good stories include a problem or tension. This might be a choice the character has to make, a disagreement, or even an inner fear. The conflict pushes the story forward and makes it more interesting.

Example: A girl who wants to apologise but is too embarrassed might have an internal (mental) conflict.

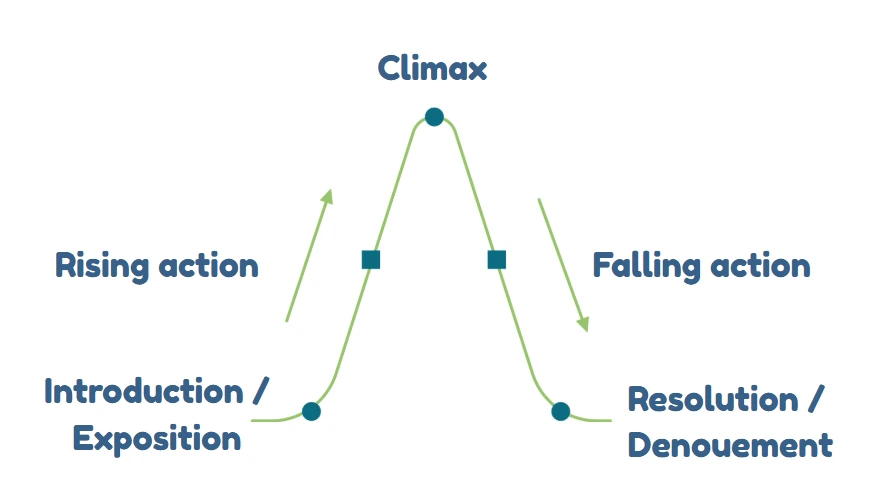

Climax

The climax is the most dramatic or emotional moment in your story – the turning point. It’s often where a choice is made, a truth is revealed, or something big happens.

Example: A boy finally admitting the truth about what he broke.

Tone/Mood/Atmosphere

These words describe the overall feeling that a piece of writing has – it might be joyful, worried, eerie, calm, or something else! How a story or description feels mostly depends on the language you use.

Example: Describing a dark, silent forest can create a tense mood.

Dialogue

This is when characters speak. What they say can show their personality, move the story forward, or build tension. However, too much dialogue can mean that you don’t describe things in detail, so aim for a balance between dialogue and descriptive sentences.

Tip: Keep it realistic and meaningful – small talk can be very boring in a story! Additionally, make sure that you use the correct punctuation. Punctuation rules for dialogue can be tricky!

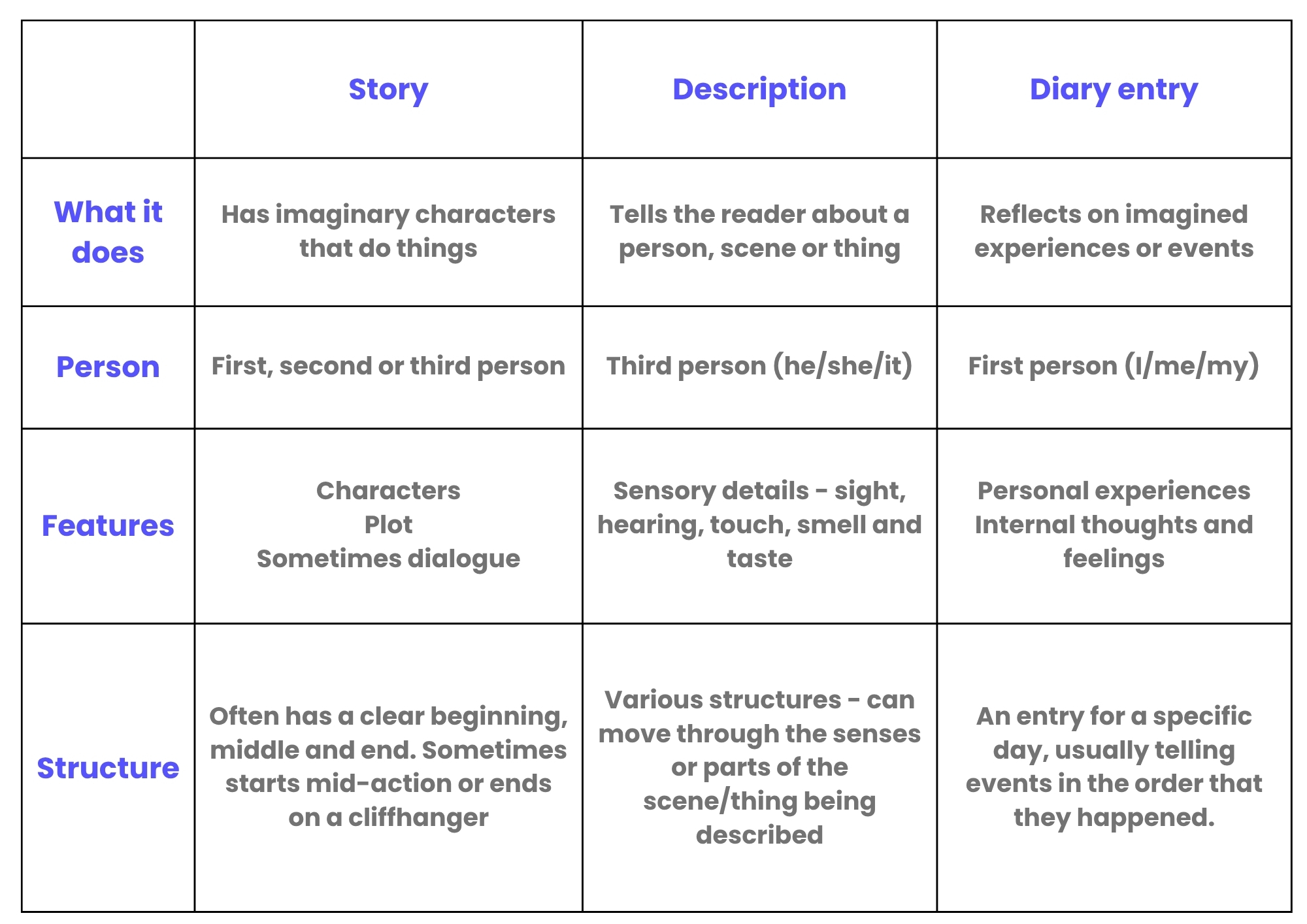

The type of fiction text that your child is asked to write will have a big impact on their writing. Children may encounter a variety of writing tasks for the 11+ and beyond, so it’s helpful to know the differences between them. Here’s a breakdown of the three main types of fiction text that your child may need to write:

Let’s take a look at some examples to show the differences more clearly.

All three of the following examples are all about a storm, but they are written in very different ways.

Story extract:

The storm broke just as she reached the edge of the field. Rain pelted the ground, turning dry soil to mud in seconds. She ran, head down, as thunder rolled above her and lightning lit up the path ahead. Her shoes slipped and skidded, but she kept going. Behind her, the wind roared through the trees, chasing her with a voice that sounded almost human. She didn’t stop until she reached the safety of the old stone wall, her breath ragged and hands shaking.

- This story is written in third person (she)

- It’s about a made-up character (the girl/woman)

- There’s a clear plot – the storm starts, she runs, and she reaches shelter

Tips:

- It’s possible to write an effective story in the present tense, but it’s usually easier for children to write in the past tense.

- Although most children are tempted to include lots of dialogue in stories, it’s often more effective to limit the amount of speech or avoid using it altogether – it should only be used when it moves the plot forward or tells the reader something about the characters.

Description extract:

Large, grey clouds thundered across the sky like a herd of angry elephants. Rain lashed the pavement, drumming loud and fast. The trees trembled as the wind howled, tugging at their branches like it wanted to tear them free. Water trickled down walls and pooled around drains. The air smelt sharp and heavy, filled with damp earth and something electric. Above, lightning cracked the sky open. For a second, everything turned white. Then came the thunder, rumbling low and dark through the empty streets.

- This description is written in third person

- It has no characters and no clear plot

- The only thing that happens is the storm, and the writer tries to get the reader to imagine what it is like

- The description includes sensory details:

- Sight – clouds, rain, trees, water, lightning

- Sound – drumming, loud, howled, rumbling

- Touch – tugging, tear, trickled, damp

- Smell – sharp and heavy, damp earth

Diary extract:

Dear Diary,

Today I got caught in the middle of the storm. It hit so suddenly. One second, I was walking home, and the next, the sky turned dark and the rain started hammering down like it had been waiting all day. I tried to run, but the wind pushed me sideways and the mud made my feet slide everywhere. Thunder crashed right above me. It was so loud that I felt it in my chest. I ducked behind the old stone wall by the path, heart thumping, completely drenched. The cold got into my bones. But even though I was soaked and shaking, there was something amazing about it. The sky was alive. It felt like the world had forgotten everything else, just for a moment, to let the storm speak.

- This diary entry is written in first person (I, me, my).

- It has a main character (narrator) describing their personal experiences.

- It shows the narrator’s inner thoughts and feelings – ‘…there was something amazing about it. The sky was alive. It felt like the world had forgotten everything else, just for a moment, to let the storm speak.’

- Events from the day are told in the order that they happened.

Using Language Features in Fiction Writing

Good fiction writing creates a picture in the reader’s mind and helps them feel part of the scene. One of the best ways to do this is by using carefully chosen language. A few well-placed language features can turn a plain sentence into something much more powerful.

Tip – See the ‘Language Features’ topic for more information about the types of language features your child may wish to use.

Take this simple example from a fictional diary entry:

Without language features:

There was no noise in the forest. I walked through the trees and felt scared.

This tells us what’s happening, but it doesn’t create much atmosphere. The setting feels flat, and we’re simply told that the narrator is scared rather than shown how they feel.

Now compare it with this version…

With language features:

The forest was silent, holding its breath. I crept through the tangled trees, my heart thudding like a drum in the dark.

What makes this version better?

- The forest was silent, holding its breath’ uses personification, making the forest feel alive and tense. It helps create a mysterious or eerie mood.

- ‘Crept’ is a more precise and interesting verb that shows how the narrator is moving (carefully and nervously). This tells us more than just saying ‘walked’, as it shows the narrator’s emotions.

- ‘Tangled trees’ uses alliteration and adds a sense of difficulty or confusion in the setting.

- ‘My heart thudding like a drum’ is a simile that shows the narrator’s fear in a vivid way, rather than just saying ‘I felt scared’, which is less interesting.

- ‘In the dark’ adds to the atmosphere and keeps the mood tense.

By using better vocabulary, adding detail, and using language features like similes and personification, the second version feels more dramatic and draws the reader into the scene.

Encourage your child to aim for this kind of writing by:

- Zooming in on a small moment

- Choosing words carefully

- Using language features that suit the intended mood

They don’t need to overdo it – just two or three strong language features in the right place can make a big difference.

Structuring Fiction Writing

Structure is the way your fiction text is organised. It’s the order of events or descriptions, the way you reveal information, and the emotional journey you take the reader on.

When writing fiction, most children focus on what happens – the plot, the characters, and the setting. All of that is important, of course. But what really sets a strong piece of writing apart is how you decide to structure it.

Let’s take a classic example.

You probably know the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears: Goldilocks wanders into a house, eats some porridge, breaks a chair, falls asleep, and gets caught by the three bears that live there. The end.

But what if the story started like this instead?:

Goldilocks was running. Her breath came in sharp bursts as branches tore at her arms. Behind her, the roar of something huge echoed through the trees. She didn’t look back. She couldn’t. She stumbled into the clearing, the scent of porridge still clinging to her clothes.

Same events. Completely different structure. The reader is thrown into the action, and now they’re desperate to know why she’s running.

Encourage your child to try starting their story, description or diary entry at an interesting point, and get them to focus on just one moment, one decision, or one problem. You’ll notice that not much actually happens in the paragraph above – there’s really only one action (Goldilocks running away). The writing is effective because this one action is described in detail.

Strong fiction texts don’t just rely on interesting plots or clever techniques; they also rely on well-crafted paragraphs.

Good fiction writing uses paragraphs to show when something changes. Your child should start a new paragraph when they move on to a new thought, action or focus.

Paragraphs can also control the pace of a fiction text (how quickly or slowly events or descriptions unfold) and build tension.

Longer paragraphs build detail slowly:

‘Ella stared at the letter, her fingers tightening around the edges. It had been stuffed through the letterbox earlier that morning, but she hadn’t opened it until now. There was something final about it, as if the paper itself carried an immense weight. The corners were slightly curled and damp from where it had been lying on the mat.’

Shorter paragraphs increase the pace, adding drama or surprising the reader:

‘She froze. The back door was wide open.’

Top Tips for Paragraphs:

- New paragraph = new moment, idea, speaker or shift

- Use short paragraphs for sudden realisations, shocks, key ideas, or high tension

- Use long paragraphs to describe things or explore thoughts in more detail

- Don’t overdo short sentences – give important moments room to stand out

- Vary your sentence lengths within the paragraph to change the pacing

Fiction Writing Example Questions

Q1 – Write the opening of a story about a child who discovers something strange at the bottom of their garden.

Aim to write 4-5 sentences.

Example answer:

Jamie crouched by the hedge, heart thudding. There, half-hidden beneath the ivy, was a narrow wooden door. It wasn’t there yesterday. He reached out, brushing away the leaves. The metal handle was cold, and something about it made his fingers tingle.

Tip: Try to use interesting words and include adjectives and adverbs (describing words) in your writing.

Q2 – Describe a mysterious forest.

Aim to write 4-5 sentences.

Example answer:

The trees loomed overhead, their twisted branches creaking in the breeze. A damp, earthy smell clung to the air. Somewhere above, a bird cried out, sharp and lonely. The ground squelched with each step, and the cold mist clung to her skin like spiderwebs.

Tip: Try to appeal to the reader’s five senses when you’re describing. It’s also a great idea to use similes and metaphors.

Q3 – Write a diary entry from someone who has just finished their first day at a brand new school.

Aim to write 4-5 sentences.

Example answer:

Dear Diary,

Today was my first day at Park View. I felt like I had a thousand butterflies in my stomach. The corridors were packed, and every classroom looked the same. I forgot my timetable and ended up in the wrong lesson, but a kind boy called Yusuf helped me find my way. By the end of the day, I realised that I’d smiled for most of the day, made a friend, and learned that Year 7 isn’t quite as scary as it seems.

Tip: Remember to focus on inner thoughts and feelings when writing diary entries.

Q4 – Improve this sentence:

The wind blew through the trees.

Example answer:

The wind rushed through the trees, making the leaves hiss and the branches sway like dancers.

Tip: Try adding more interesting vocabulary, or using a language feature like a simile.

Q5 – Improve this sentence:

I was scared.

Example answer:

My hands were shaking and my stomach twisted. I couldn’t think straight, and every sound made me jump.

Tip: It’s better to show how a character is feeling rather than just telling the reader.

Q6 – Improve this sentence:

She walked into the house.

Example answer:

She pushed the door open slowly. The hallway was dark, and the silence made her skin crawl.

Tip: Don’t just say what happens. Try to create a specific mood or tone by saying how it happens and describe what it’s like.

Q7 – Improve this sentence:

The dragon was big and scary.

Example answer:

The dragon towered over the village, its eyes glowing like embers and smoke curling from its jaws.

Tip: Try to use interesting vocabulary to describe things in detail.

Q8 – Here’s the opening of a story:

‘On Saturday, Ewan woke up, ate breakfast, and decided to go exploring. He packed his bag and set off.’

Write a new opening that starts in the middle of the action.

Example answer:

The ground gave way beneath Ewan. He tumbled, landing hard on the tough gravel. When he looked up, he realised that he was no longer in the forest.

Tip: It can be effective to start stories or diary entries with a sudden discovery or problem.

Q9 – Here’s the opening of a diary entry:

‘Dear Diary,

Today was strange. I went to the park and saw something unusual.’

Write a new opening that starts with the narrator’s thoughts or feelings.

Example answer:

Dear Diary,

How do you explain something you’re not even sure was real? I keep replaying it in my head, but I still can’t believe it…

Tip: Starting with an emotion, question or thought can sometimes be more effective than jumping straight into the action.